|

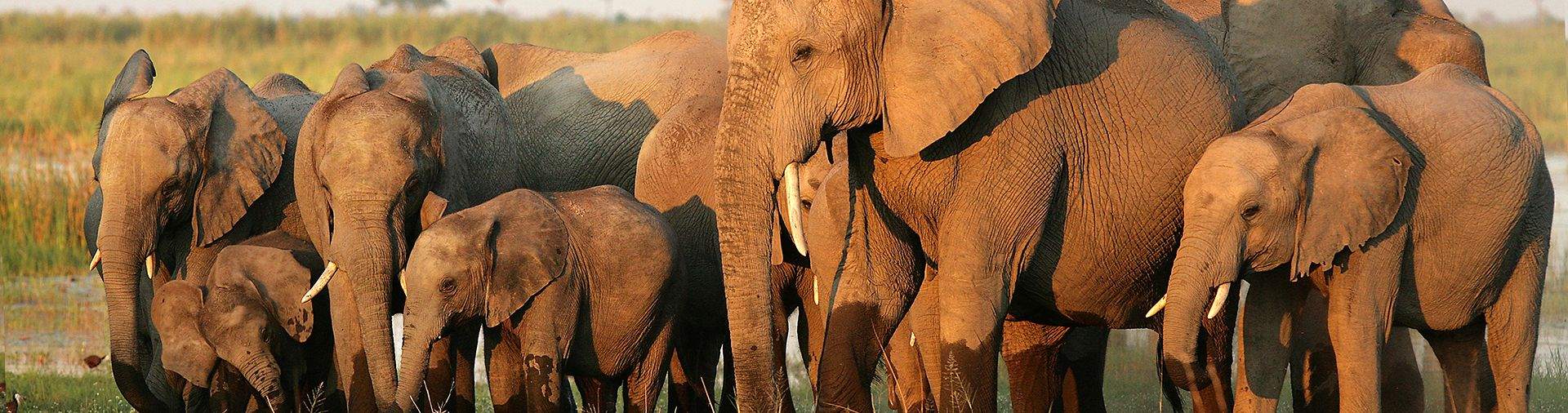

London has overshot its air pollution allowance for the year, for the eighth year in a row, before the start of February. This has taken more time than the previous year when it took less than a week to break the allowance. This is just one of the news items that appear in headlines that spur the safari industry to become more sustainable and to protect the untouched beauty of the habitats and the wildlife within them that guests come to see. In this, the second of our sustainability blogs, we will focus on East Africa. Properties in the spotlight are Little Governors’ Camp in Kenya’s Maasai Mara and Singita in the Grumeti & Northern Serengeti of Tanzania. Governors’ camp switches to solar Little Governors’ Camp is smaller than its larger sister, Governors’ Camp. Built in 1976, it comprises 17 tents near the Mara River in the north-eastern part of the Maasai Mara Reserve in Kenya. It is only accessible by a boat trip across the river, with vehicles left behind on the bank, exhibiting the value Governors’ place on peace and tranquillity for their guests. The tents surround an active watering hole that is visited regularly by elephants and the camp’s resident warthog family, that are known to walk between the tables at mealtimes! In 2017, the camp was converted to run completely on solar energy. By installing solar panels on the roofs of the staff accommodation, the camp’s back-of-house operations and all guest needs are met by the power of the blazing African sun. Each guest tent also has a solar water heater discretely placed behind the tent. The camp has a “carbon counter” at reception that records how much is saved by turning to solar energy. Earlier in the year Governors’ had also made big moves to reduce their plastic use, following a ban on the use of plastic bags in the country. If a person is caught with a plastic bag the penalties can be harsh. Governors’ also invested in reverse osmosis water filtration systems providing guests with clean drinking water that does not need to arrive at camp in plastic bottles. As is the trend with many African camps now, each guest is given a refillable metal water bottle on arrival. There are water refills around the camps and each tent has glasses with their own filtration system too. This also allows the camps to use fine hand-blown glass jugs to fill guests water glasses at meals instead of plastic bottles. Little Governors’ have also changed their bathroom amenities packaging. The rooms have all the locally made organic luxuries expected and they are now in metal dispensers rather than plastic. Singita Wildlife fees introduction At the end of 2017 Singita changed their policy regarding Tanzanian Government wildlife and conservation charges. They had been paying these amounts on behalf of all guests from their accommodation charges, but with their conservation programs in the region becoming more successful and more opportunities emerging that require extensive funding, this policy has changed. As with other wildlife areas in the region, these government charges will now therefore be charged to visitors – applicable only to new bookings. Wildlife fees are paid for every person and vehicle that enters a designated Wildlife Management Area in Tanzania. The fee is paid to the Community Wildlife Management Areas-Consortium. Recognised by the government in 1998, the consortium ensure that the rich wildlife and natural areas of the country are protected, managed and are of benefit to the local communities surrounding them. Some of the things the organisation has achieved to date include; uniting communities in the Wildlife Areas, giving them a stronger voice to bring to discussions with government; attracting tourism investment of over 4.3 million USD to 12 different Wildlife Management Areas and bolstering the anti-poaching efforts by training local scouts and providing them with the power to make lawful arrests. In 2003 Singita was granted custodianship of the 350,000 acres of the unique Grumeti reserve in the western Serengeti National Park. The animal numbers in the area had been severely depleted by poaching, wildfires and invasion by alien species. In the years since the area has nearly returned to it’s natural state. The full works of the Singita Grumeti Fund are worthy of a whole blog post of their own and so we will keep it concise here. The Singita Grumeti Fund has five main areas of focus; Conservation, Anti-Poaching & Law Enforcement, Community Outreach, Research & Monitoring and Relationships and the occasional special project also.

They have achieved the following “highlights”:

4 Comments

In recent news President Donald Trump has denounced, via his twitter page, his own political party for their plans to remove the ban prohibiting imports of elephant trophies from Zimbabwe. This highly contentious topic is so multi-faceted it is hard to make sense of, so here we will try to give a simplified view of both sides of the discussion. The ban has been halted to both Zimbabwe and Zambia but we’ll mainly focus on Zimbabwe. To keep matters simple we will not mention lion trophies in this article, we’ve spoken about the illegal trade of this species in a previous blog post. To start it is important to know an elephant trophy is not a specified item. It can be the head or any other part of the body, for instance the tail or a foot of the animal. Many people in the US are not aware that the import of ivory into the US is lawful providing the correct documentation proving it is a sport-hunted trophy is provided. Sport-hunting of many animal species in Africa – including elephant – is legal. However, onward sale of the trophy once in the US is not allowed. In 2014 the Obama administration banned the import of elephant trophies from both Zimbabwe and Zambia. This was due to their poor records of elephant data and numbers and regulation of the hunting industry. A survey of the African continent’s elephant numbers published in 2016 showed the declines in population numbers in both countries. Zambia had a decrease in population numbers of 11% in the decade from 2005-2015, with one National Park’s numbers declining from 900 in 2004 to just 48 in 2015. While Zimbabwe had the second highest population number on the continent in the recent census, the decline was 10%. These percentage declines are greater than the replacement number of breeding elephants (about 6%), and so the total population in each country is declining. The African continent’s total elephant population numbers dropped nearly 30% from 2007 to 2014 – with the total now standing at an alarming 352 000. Causes are thought to be mainly poaching for the illegal wildlife trade and in some cases, habitat destruction. The reason the import ban into the US is so important is because it is the largest importer of trophy hunted animals in the world today. Within that industry from 2005 to 2010 2,963 violations were documented for the import of sport hunted trophies to the country. Just over half were relating to endangered species with only 14 people serving jail time and 546 having to pay fines from $25 to $390,700. With these figures of prosecution there is reasonable chance that a trophy that violates import law will not result in more than a minor fine and so may propagate the illegal wildlife trade. The country with the biggest illegal ivory trade in the world is China. In recent years this country was the largest importer of trophy hunted ivory from Zimbabwe. Many are sceptical that this is not a part of the illegal wildlife trade for which China is infamous. Both Zambia and Zimbabwe have proposed to the US Fish & Wildlife Services (USFWS) that they now have the numbers, the correct means and plans to monitor and maintain their elephant population numbers. This is what led to the Obama-era ban being lifted and the USFWS starting to sell permits for elephant trophy imports from these countries. President Trump has paused the removal of the ban, and thus stopped trophy permit sales, for both countries and many wonder why his administration had gone so far in the plans with him seemingly unaware of the facts.  Trophy hunters have been unhappy about the ban the Obama administration introduced. Conservation force, wrote an open letter in June 2017 to the Director of the USFWS to request that the importing of elephant trophies from Zimbabwe should become lawful. The letter was written to appeal the import two specific trophies and they argue that the original ban was “based on erroneous information and misinterpretation of fact and has been from the very beginning”. They have said that the lack of data from Zimbabwe at the time of the decision was due to the US not asking for it and say it was provided after the fact with no reaction. This letter also lays out the basis of the “hunters as conservationists” argument. The hunters provide money to the areas in which they hunt and so to the communities, they provide employment in the industry. A trophy hunt to kill an African elephant can be up to $60,000, in a country where the average monthly earnings is around $350.00. This amount is more than a photographic tourist would pay to visit the area, meaning the number of tourists and the impact on the environment is less. The money is said to not only serve the local communities but also allows large swathes of the continent to be protected natural areas for the animals, areas that are not part of the national parks. Not every animal in a herd will be shot, in fact for trophy hunting they will choose an animal at the end of it’s life, partly for the most impressive trophy, but also as this will have the least impact on the ecosystem. However removing the strongest and biggest animals from the population is contrary to evolution and hunting, with poaching has impacted the gene pools of the populations. The best elephant trophy is the largest with the biggest tusks. This individual will most likely be the most dominant in an area and likely to mate with the most females and pass on superior genetic material. If this male is killed before he has fulfilled his mating potential then there will be less of his genetic information in the gene pool and more of smaller, weaker individuals. This happens repeatedly until there is very little of the ‘large’ genes left and the effects can be seen within the elephant populations now after the big game hunting days of the 1900s. The other important aspect of killing the mature bulls is the impact on the younger bulls. These trophy bulls will be in their late 40s, 50s and even 60’s. They have decades of experience from which younger bulls learn. The social experience is highly important in the same way it is for young humans to learn to behave, learning manners, when to get upset and when not to. There is also ecological knowledge they pass on, for instance where the water is found in a drought and how to get there. Removing that knowledge affects the next generation; it will be damaging to the whole population and eventually will have a drip down effect for years to come. Responsible hunting farms will be sure to manage their populations correctly and ensure the surrounding communities benefit from the business, but the problem comes in with corruption. Africa is rife with corruption and when companies from America try to apply the systems and principles that apply in the US it often falls flat of achieving the desired effects. The systems in Zimbabwe, which are in place to ensure the communities receive money from the legal hunts are in fact managed, whether deliberately or not, so poorly that the local people only occasionally benefit from the hunts. With the local people being so poor and gaining nothing from the elephants but trouble with crop damage, there is little wonder that so many turn to poaching to feed their families.

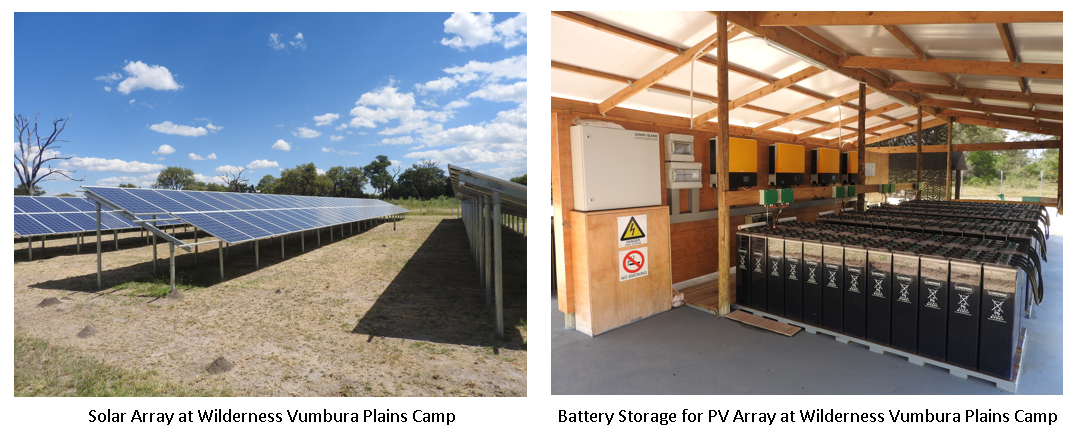

This is a debate that will no doubt continue into 2018 and we will keep you updated on developments and the repercussions thereof. In November the latest global carbon emissions report for 2017 was released. For the first time in 3 years the global carbon output increased. China is the largest contributor to the increase. The drought in the region is thought to be the cause, due to reduced energy contribution from hydroelectric power. But China is not the only country to have affected the level of these emissions; the USA and the EU both have seen lower than predicted decreases in emissions. Whilst these figures are mostly related to large-scale industry, we can all do our best to decrease where we can. As such we have been inspired to show you how the safari industry is ensuring that their operations and visitors have the smallest carbon footprint possible, thus mitigating the negative impacts on the environment, wildlife and local people. It is important to state from the outset that there is a big difference between CONSERVATION and PRESERVATION – two terms that are often confused and this creates problems when environmental and wildlife issues are debated. Preservation is quite simply a ‘hands-off’ approach where there is no input, management or ‘use’ of a resource (be it fossil fuels, water, wildlife or a habitat or environment in general. In other words, for a wildlife area there would be no infrastructure, tourism activities, interventions or management of any kind. Conservation, on the other hand, is the ‘sustainable utilisation of a natural resource’. Safari tourists staying at safari lodges and wanting park rangers to help sick or injured animals are therefore intrinsically part of a conservation system and cannot then as an example, argue against culling of wildlife. This provides food for thought and as such, this will be an on-going series as we receive news from different operators about their evolving systems and methods as new technology plays a role in new and upgraded lodges, hotels and camps and revamped legislation for ’greener and carbon-neutral scores’ is brought to bear on the industry. In this post we will look at two camps in the Okavango Delta region of Botswana, a country renowned for its pioneering sustainability and conservation methods. Botswana has long been concerned with the protection of its spectacular wilderness areas. A leader in the field of conservation, their method is simply to have a small high-end tourism industry. Keeping the effects on the pristine landscape to a minimum while generating high income allows for local communities to support themselves via employment with operators. This also helps to prevent poaching as the community members’ livelihoods are now directly linked to the animals’ survival. In 2014 hunting was controversially banned nationwide, demonstrating President Ian Khama’s dedication to protecting endangered species, their habitats and one of the most unspoiled regions in the world. This high-end tourism is one of the three pillars of the economy, contributing heavily to the country’s prosperity. Beat About The Bush Tourism has always been committed to only sending our guests to operations in the Delta with proven environmental and community-focused track records. Here are two of our favourites: Chief’s Camp – Sanctuary Retreats Chief’s camp is located on Chief’s island, the largest island in the Okavango Delta named for historically the sacred hunting grounds of the Batawana Chiefs. When the floods come every year, the island is at a level above the water, many animals come here to escape the water; it is the Okavango Delta as you see in nature documentaries. The camp has recently been renovated and adds the sustainability feather to its cap. Luxury has in no way been compromised, there is wi-fi, fan and air-conditioner available in each room along with a private plunge pool for the hot summer days. If you book the new Geoffrey Kent luxury suite you will enjoy a butler, private chef and an outside boma to sit undisturbed under the stars. The key feature of the newly renovated camp is a solar farm – replacing the noisy, polluting diesel generators (now used as back-up). Built to handle the camp’s electricity requirements, the farm is large enough to support the majority of the camp’s energy needs. The solar batteries charge during the day to ensure there is electricity through the night. The effect of the solar farm is not simply removing a generator and diesel usage. Now there are no delivery trucks coming through to bring oil and gas for the generators. Decreasing the number of vehicles driving through this wetland wonderland – thereby reducing environmental impact with less tyre ruts that disrupt the flooding patterns and make the area look unsightly for years to come. Chief’s camp also has a new and very efficient, eco-friendly and self contained sewerage system to ensure that all water is cleaned before being used as ‘grey water’ or released through a wetland. It goes without saying that all detergents and cleaning products are eco-friendly and plastic water bottles have been replaced with refillable bottles from water dispensers. Sanctuary Chief’s camp YouTube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQno0IPvgEU Vumbura Plains Camp – Wilderness Safaris

Wilderness Safaris is originally from Botswana and they are leaders in the field of conservation and sustainability. This will not be the last of their camps to make our list! With 11 of their camps now operating on 100% solar energy they are dedicated to preserving the pristine and beautiful surroundings for generations to see. They operate with a policy they call the 4C’s; Commerce, Conservation, Community and Culture. Vumbura Plains Camp is located in the northern Okavango Delta and is in fact separated into two camps, one more family friendly. Each room is luxurious and is raised off the ground with a plunge pool and your own deck to watch the stars at night or the world (and maybe even some animals) pass by during the day. The camp is run fully on solar electricity, with batteries for the night and enough power for each room to have a hairdryer. This solar power also provides hot water for the entire camp. Vumbura’s conversion to solar energy is particularly relevant as it was the second largest energy consumer in the Wilderness group. The solar farm reduced the need for deliveries of oil and gas and as such the impact to the environment via soil compaction and disturbance to the environment is diminished. They have an above ground sewage plant that ensures all water used, grey and sewage is cleaned completely before it is released back to the surrounding environment. Vumbura also offer guests water bottles that are refilled from water dispensers in the camp reducing plastic waste. Photo credit: http://botswanaenergy.blogspot.co.za *Warning: this blog post contains images that some readers may find disturbing. Lions represent an essential part of the African landscape. As an apex predator, they help maintain healthy ecosystems by keeping prey numbers in check and removing diseased or weak individuals from prey populations, thus improving the overall health of these species. Lions are also of vital economic importance. As a member of the Big Five and a must-see on most tourists’ wishlists, lions and other iconic species are fundamental to South Africa’s tourism success. The total contribution of travel and tourism to the gross domestic product (GDP) of South Africa was R 402bn (9.3% of GDP) in 2016. The travel and tourism sector accounted for 1.5 million jobs or 9.8% of total employment in 2016. In June 2017, South Africa announced the legalised export of 800 skeletons (with or without skulls) from captive bred lions to Asia a year, sparking controversy from conservationists and safari operators who suggest that this decision may threaten lions and jeopardise the tourism industry. Similar to rhino horn, the demand for lion bones is stimulated by traditional medicinal uses in Asian countries. Unlike many other species in traditional Asian medicine, the use of lion bones is a relatively new trend that only became public knowledge about a decade ago. Powdered tiger bones have been used as ingredients in wine for at least 1000 years. Tiger bone wine and cake is believed to have aphrodisiac qualities and cure malaria, arthritis, other bone ailments and rheumatic conditions. No scientific merit has been associated with these claims. Following a steep decline in wild tiger populations, the species received greater protection measures, including a ban on all trade and stricter law enforcement. This provoked the use of bones from other big cats as viable substitutes, including lions, leopards, snow leopards and clouded leopards, with lion bone being the most popular due to their physiological similarities to tigers and the relative ease in accessing bones from South Africa. South Africa is the largest exporter of lion parts to China, Laos PDR and Viet Nam, with bones originating as by-products of the canned hunting industry. In South Africa, between 6000 and 8000 lions and 280 tigers are kept in captivity. Lions are primarily farmed for canned hunting (animals are bred and raised in captivity to be released into the ‘wild’ a short time before a hunt is planned). Paying hunters often keep the skins and sometimes the skulls as trophies. The bones, previously discarded, have now become a source of commercial income and are legal to trade internationally up to a certain quantity with the correct permits. It is probable that tiger bones and lion bones are passed off as one another depending on the sellers availability at that time. Wild lion numbers have declined by 43% in past two decades to an estimated 20000 lions in Africa today. This decline is largely associated with habitat loss but conservationists and leading tourism operators fear that legalised trade in captive lion bones may stimulate further declines in wild populations and discredit South Africa’s reputation as a photo-safari destination. Limited trade in lion body parts bred in captivity is legal but trade in body parts from wild lions is not permitted. Permitting some trade in animal parts can fuel market demand which may lead to poaching of wild lions and tigers, especially since wild animals are preferred over captive felids in traditional medicine. Examples of illegal poaching for lion bone have already been recorded. In early July 2017 three lions were poisoned with Temic laced baits in Limpopo National Park, Mozambique for the lion bone trade.

For more information about the lion bone trade, we recommend the following reports:

Today marks the end of South Africa’s first online rhino horn auction. The three-day auction opened on August 23rd amidst an onslaught of publicity and controversy. The auction follows the legalisation of domestic trade in rhino horn within South Africa earlier this year. International trade in rhino horn was banned in 1977 by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES) and remains prohibited today. However, domestic trade of rhino horns remained legal in South Africa until 2009 when the South African government imposed a moratorium on domestic trade in response to a rise in rhino poaching. This remained uncontested until private rhino breeders filed a lawsuit to overturn the domestic moratorium and on April 5, 2017, they succeeded by winning a court case against the South African government, thus legalising the domestic trade of rhino horn within South Africa once again. John Hume, the world’s largest rhino breeder who owns more than 1500 rhinos on his private farm, led the court appeal with safari operator, Johan Kruger. Hume also launched South Africa’s first online rhino horn auction, which is coming to a close today. Hume regularly de-horns his rhinos through a painless procedure. De-horning is done to deter poachers and has resulted in Hume stockpiling approximately five tonnes of rhino horn. This week’s auction aims to sell 264 rhino horns, totalling about 500 kg. Hume will also host a physical rhino horn auction on September 19, 2017. Rhino products can be sold to international buyers but the horns must remain within South Africa. All rhino horns are microchipped, DNA traced and entered into a national database to prevent illegal trafficking. Buyers and sellers of rhino horn are required to apply for government issued permits. South Africa is home to the world’s largest population of rhinos but is in the midst of a severe poaching crisis. Rhino horn is illegally harvested and trafficked to mostly Asian markets for traditional medicinal use. See our blog post on rhino poaching for more information. Hume argues that the auction will “raise money to further fund the breeding and protection of rhinos”. Money raised from the auction will contribute towards the spiralling security costs required to protect his rhino population. He believes that by farming rhinos as a ‘renewable resource’ (after dehorning, rhino horn grows back to its original length in two or three years), the market could be flooded (whenever international trade bans are lifted), thus reducing illegal poaching pressures. Many conservationists are opposed to the domestic sale of rhino horn within South Africa and argue that because there is little use or demand for rhino horn nationally, purchases may ultimately end up being trafficked to international markets. Legalisation of rhino horn trade within South Africa may serve as a cover for black market sales internationally and further fuel rhino poaching by creating a surge in demand that cannot be met. There are concerns that the measures put in place to track the horns and keep them within South Africa may be counterfeited and in partnership with corrupt officials, horn will be illicitly traded internationally. Advertisements for the online auction and the auction’s website were translated into English, Mandarin and Vietnamese, further provoking suspicions. Some conservationists argue that rhinos should not be farmed, as the current population of privately owned individuals cannot meet the high product demand on a regular basis. Instead, efforts should be focussed on protecting rhinos in the wild. The opposition has been so severe that hackers closed down Hume’s auction website for several days prior to the auction’s launch.

As the auction comes to a close later today, the world waits to hear the outcome and its implications for international rhino conservation. *Warning: this blog post contains images that some readers may find disturbing. Many of our guests commence their safari with a basic understanding of rhino and elephant poaching. Nevertheless, they are often keen to learn more and to help if possible. This is especially true after having the opportunity to view these majestic animals up close in their natural environment. What is poaching? Poaching is the illegal taking of wildlife in violation of local, national or international laws (for more on the difference between poaching and hunting, click here). Animals are poached for numerous reasons with dire ecological consequences. Hunting for bushmeat consumption, ornamental use and medicinal purposes, as well as trapping for the pet trade, is threatening 301 terrestrial mammal species with extinction worldwide. Unsustainable local consumption of bushmeat and international trafficking of body parts such as tusks, horns, bones or scales poses a serious risk to wildlife in developing countries where human populations are frequently escalating and poverty is rife. International wildlife trafficking is fuelled by demand from more developed nations. Why does rhino and elephant poaching occur? Rhino horn is used in traditional medicine in China and several other Asian countries. Rhino horn is believed to treat hangovers, impotence, fever and cancer. However, it has been scientifically proven that rhino horn, which is made from keratin, has no medicinal properties. Rhino horn is increasingly used as a status symbol of a person’s wealth and power. Elephants are frequently killed for their ivory tusks which are used for ornaments and jewellery. Despite bans on the international trade in rhino and elephant parts, these species are being killed at astonishingly high rates. The demand for rhino horn is so high that it worth is more than gold pound per pound. High demand of these limited and difficult to acquire products has resulted in intricate international crime syndicates with access to high-powered technology and weaponry. Those conducting the poaching on the ground (and at the most risk of being caught) are often locals whose involvement may be driven by challenging socioeconomic conditions such as poverty and unemployment. Rhino and elephant poaching is frequently associated with African countries, however it is a global epidemic. One horned rhinos in Chitwan National Park, Nepal have been recent victims of poaching. A rhino was killed for its horn in a French zoo earlier this year. This was the first such incident in Europe. What is the current situation for rhinos and elephants? Rhinos There are five species of rhinos in the world and at the end of 2015, it was estimated that there are 30 000 rhinos across all extant species. In Africa, the black rhino is estimated at between 5 042 and 5 458 individuals and the Southern white rhino is estimated at between 19 666 and 21 085 individuals. South Africa has the largest population of rhinos in the world and it is home to 74% of the African rhino population. In 2016, 1 054 rhinos were poached in South Africa alone. This is a rate of nearly three rhinos a day. This is the second year in a row that the number of rhinos poached in South Africa has declined (1 215 in 2014 and 1 175 in 2015), providing some hope of a reversal in trends. In the first six months of 2017, 529 rhinos were poached in South Africa. Although this is 13 less than the same period last year, this rate is still worryingly high. The majority of South Africa’s rhino poaching incidents happen in Kruger National Park. 243 of the 529 rhinos killed between January and June 2017 occurred in Kruger. Reports in 2017 show that rhino poaching in Kruger is down by 34% compared to 2016 but there is an increase in the number of poaching incidents in other parts of the country, especially the province of Kwa-Zulu Natal. Elephants There are an estimated 35 000 – 40 000 wild Asian elephants. A large-scale census spanning 18 African countries counted 352 271 African elephants in 2014. The findings from this robust survey indicates a 30 per cent decrease in the African elephant population (equal to 144 000 elephants) between 2007 and 2014 and equates to an annual loss of nearly 30 000 elephants. At this current rate of decline, half of the Africa’s elephants will disappear in nine years. Tanzania, Mozambique, Angola and Cameroon were identified as some of the worst affected areas in the 2014 census. A surge in poaching in the past decade is largely responsible for elephant population declines. In Kruger National Park, South Africa, two elephants were poached in 2014, 22 elephants in 2015, 46 elephants in 2016 and 30 elephants in the first six months of 2017 alone. What can I do to help?

Although these figures are critically high, it is not too late to take action. The Southern white rhino was depleted to only 50 – 100 in the wild in the early 1900s, but now it is the most populous rhino species at approximately 20 000 individuals. Applied conservation efforts and multifaceted approaches are required to reverse the trends in rhino and elephant poaching. Here are several lists outlining how individuals can support this work and make a difference: - 15 things you can do to help stop rhino poaching - Save the Rhinos Get Involved page - What can I do to help elephants? - Six ways to help elephant |

AuthorTrevor Carnaby Archives

March 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed